No matter where you are in the United States, chances are you can find harmful PFAS compounds in the water near you.

By Lynne Peeples for Ensia | @ensiamedia | @lynnepeeps

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a nine-month investigation into drinking water contamination across the United States. This series is supported by funding from the Parks and Water Foundation. Read the premiere story, “Thirst for Solutions,” here.

Tom Kennedy learned about the long-term contamination of his family’s drinking water about two months after he was told his breast cancer had metastasized to his brain and was terminal.

The trouble fouling his taps: per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a widespread class of chemicals invented in the mid-1900s to add desirable properties like stain and stick resistance to shoes, cookware, and other everyday items. Manufacturers in Fayetteville, North Carolina, had been dumping them into the Cape Fear River—a source of drinking water in the area—for decades.

“I was furious,” says Kennedy, who lives in nearby Wilmington. “I made the connection pretty quickly that PFAS might have contributed to my condition. Although there’s nothing I can prove.”

The bad news happened more than three years ago. Kennedy, who has outlived his prognosis, is now an active advocate for tighter PFAS regulation.

“PFAS are everywhere,” he says. “It’s really hard to get any change.”

Breast cancer survivor Tom Kennedy has become an outspoken advocate for tougher PFAS regulations after the chemicals were found in the river that supplies his drinking water. Photo courtesy of Tom Kennedy.

Indeed, various forms of PFAS are still used in many industrial and consumer products—from nonstick pans and stain-resistant carpets to food wrappers and firefighting foam—and have become ubiquitous. The compounds enter the environment wherever they are made, dumped, discharged, or used. Rain can wash them into surface drinking water sources like lakes, or PFAS can gradually move through soil to reach groundwater—another important source for public water systems and private wells.

For the same reasons the chemicals are prized by manufacturers—they resist heat, oil, and water—PFAS also persist in soil, water, and our bodies.

Research suggests that more than 200 million Americans may be drinking water contaminated with PFAS. As studies continue to link exposure to a long list of potential health consequences – including links to susceptibility to Covid-19 – scientists and advocates are calling for urgent action from both regulators and industry to limit the use of PFAS and take steps to ensure compounds already in the environment stay out of drinking water.

Thousands of Chemicals

PFAS date back to the 1930s and 1940s, when scientists at the DuPont and Manhattan Projects accidentally discovered the compounds. Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company, now 3M, soon began producing PFAS as a key ingredient in Scotchgard and other nonstick, waterproof, and stain-resistant products.

Thousands of different PFAS chemicals emerged in the decades that followed, including the two most studied versions: PFOS and PFOA. Oral-B began using PFAS in dental floss. Gore-Tex used it to make waterproof fabrics. Hush Puppies used waterproof leather in shoes. And DuPont, along with its subsidiary Chemours, used the compounds to create its popular Teflon coating.

Science shows links between pest-free zone exposure and a range of health outcomes, including increased risks of cancer, thyroid disease, high cholesterol, liver damage, kidney disease, low birth weight, immunosuppression, ulcerative colitis, and pregnancy-induced hypertension. “PFAS really seem to interact with the full range of biological functions in our bodies,” said David Andrews, senior scientist at the nonprofit Environmental Working Group (EWG, a collaborator on the report. “Even at levels that the average person has in this country, these chemicals can have an impact.” PFAS have been used for decades in common items like cookware and food wrap. © iStockphoto.com | woottigon | ia_64

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has even issued a warning that exposure to high levels of PFAS could increase the risk of Covid-19 infection, and has noted evidence from human and animal studies that PFAS could reduce the effectiveness of vaccines. PFAS known as PFBAs are raising particular concerns in light of the global pandemic. Philippe Grandjean, a professor of environmental medicine at the University of Southern Denmark and at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and colleagues recently found a positive correlation between the severity of Covid-19 symptoms and the presence of PFBAs in individuals’ blood, according to their non-peer-reviewed preprint paper published in May 10.

“There are a lot of potential side effects. For me, the interference with the immune system is the most important,” Grandjean said. “Our data shows that the immune system is affected at the lowest levels of exposure.”

Catastrophe

Once PFAS enter the environment, the compounds have the potential to persist for a long time because they are not easily broken down by sunlight or other natural processes.

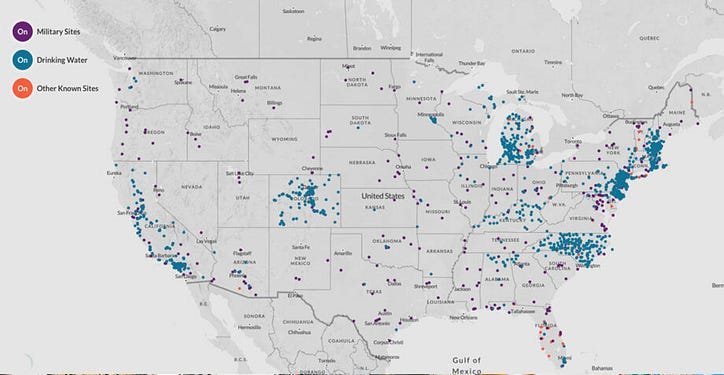

PFAS are contaminating soil and water across the United States. Copyright © Environmental Working Group, www.ewg.org. Reproduced with permission.

2,199 / 5,000

Legacy and ongoing PFAS contamination is occurring across the United States, particularly at or near sites associated with firefighting training, industry, landfills, and wastewater treatment. Near Parkersburg, West Virginia, PFAS has leached into drinking water supplies from a DuPont plant. In Decatur, Alabama, a 3M manufacturing facility is suspected of discharging PFAS, contaminating residents’ drinking water. In Hyannis, Massachusetts, firefighting foam from a firefighter training academy is a likely source of well water contamination, according to the state. The use of PFAS-containing materials such as firefighting foam at hundreds of military sites across the country, including one on Whidbey Island in Washington State, has also contaminated many drinking water supplies. “It works well for fires,” said Donald (Matt) Reeves, an associate professor of hydrogeology at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, who studies how PFAS move around and persist in the environment.

It can be an almost endless loop, Reeves explained. Industry might dump these compounds into a waste stream that leads to a wastewater treatment plant. If that facility isn’t equipped with filters that can trap PFAS, the chemicals could go directly into drinking water supplies. Or a wastewater treatment facility might create sludge with PFAS that’s applied to soil or dumped in a landfill. Either way, PFAS can escape and find its way back to the wastewater treatment plant, repeating the cycle. The compounds can also be released into the air, leading in some cases to PFAS settling on land, where it can seep back into drinking water supplies.

He said his research in Michigan echoes a broader trend across the U.S.: “The more you test, the more you find.”

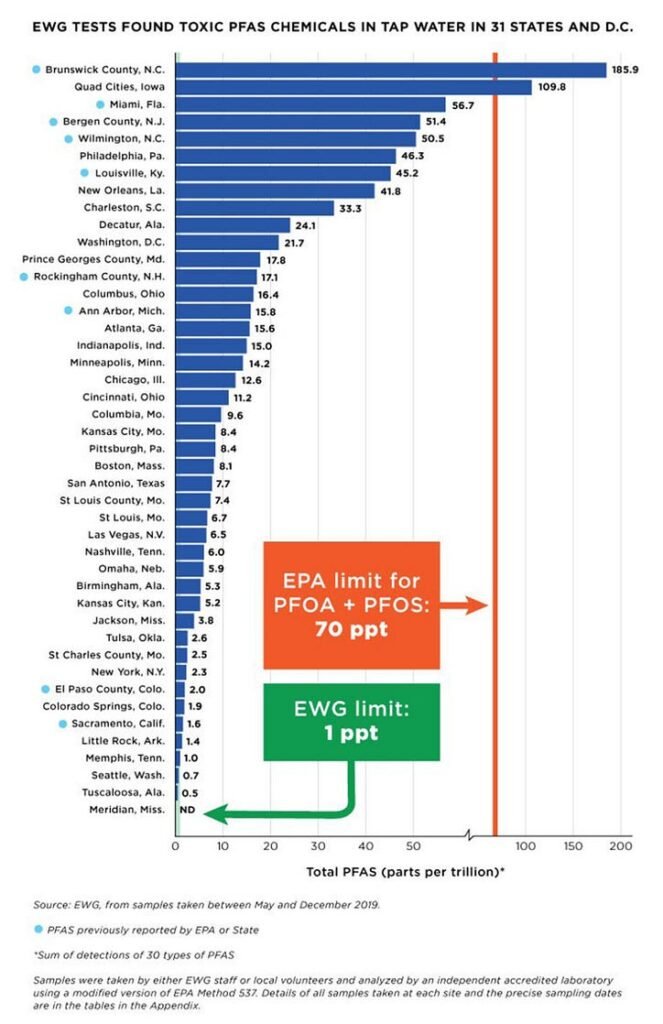

In fact, a study by scientists from EWG, published in October 2020, used state testing data to estimate that more than 200 million Americans may have PFAS in their drinking water at concentrations of 1 part per trillion (ppt) or higher. That’s the recommended safety limit, according to some scientists and health advocates, and is equivalent to one drop in 500,000 barrels of water.

Of 44 drinking water samples tested last year, the Environmental Working Group found concerning levels of PFAS in 41. Copyright © Environmental Working Group, www.ewg.org. Reproduced with permission.

“This really highlights the extent to which these contaminants are present in drinking water across the country,” said EWG’s Andrews, a co-author of the paper. “And in some ways, that’s not a big surprise. It’s nearly impossible to escape drinking water contamination.” He references research from the CDC that found the chemicals in the blood of 98% of Americans surveyed.

Regulation is inconsistent

U.S. chemical manufacturers have voluntarily phased out the use and emissions of PFOS and PFOA, and industry efforts are underway to reduce ongoing contamination and clean up past contamination – even if companies don’t always agree with scientists about the health risks involved.

Sean Lynch, a spokesman for 3M, said: “The weight of scientific evidence from decades of research does not show that PFOS or PFOA are harmful to humans at current or historical levels.” However, he noted that his company has invested more than $200 million globally to clean up the compounds: “As our scientific and technological capabilities evolve, we will continue to invest in technology Advanced cleaning and control and working with communities to identify where this technology can make a difference. ”

Thom Sueta, a spokesperson for Chemours, noted similar efforts to address past and present emissions and emissions issues. The company’s Fayetteville plant discharged large amounts of the PFAS compound GenX, contaminating the drinking water of Kennedy and about 250,000 of his neighbors.

“We continue to reduce PFAS loading into the Cape Fear River and began operating a significant groundwater collection and treatment system at the site this fall,” Sueta said in an email.

A big part of the challenge is that PFAS is considered an emerging contaminant and therefore not regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

But most of the ongoing PFOS and PFOA contamination appears to come from previous uses that are reintroduced into the environment and into people, Andrews noted.

A big part of the challenge is that PFAS is considered an emerging contaminant floats and, as such, is not regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In 2016, the EPA set a non-binding health advisory limit of 70 ppt for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water. The agency proposed federal regulations on the contaminants in February 2020 and is currently reviewing comments with plans to make a final decision this winter.

Several U.S. states have set drinking water limits for PFAS, including California, Minnesota, and New York. Michigan’s regulations, which cover seven different PFAS compounds, are some of the most stringent. Reeves of Western Michigan University says the 2014 lead contamination crisis in Flint heightened the state’s focus on safe drinking water.

But the lack of uniformity across the country has created confusion. “PFAS regulations still vary,” said David Sedlak, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. “States all have different ideas, and that’s not necessarily a good thing. People are not sure what to do.”

The Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council, or ITRC, a coalition of states that promotes the use of new technologies and processes to treat the environment, is working to compile evidence-based recommendations for PFAS regulation in the absence of federal action.

University of Southern Denmark and Harvard University professor Grandjean suggests the safe level of PFAS in drinking water may be around 1 ppt or less. The European Union’s latest risk assessment, which Grandjean says corresponds to a recommended limit of about 2 ppt for four common PFAS compounds, is “probably close,” he says. “It’s not a precautionary limit, but it’s certainly much closer than the EPA.”

GenX, introduced by DuPont in 2009 to replace PFOA, is part of a newer generation of short-chain PFAS designed to have fewer carbon molecules than the original long-chain PFAS. They were initially thought to be less toxic and more quickly eliminated from the body. But some evidence is mounting: Studies suggest that these cousins may pose many of the same risks as their predecessors.

“The family of PFAS chemicals that are in commercial use is much broader than the small group of compounds that the EPA is considering regulating,” Sedlak says. “The focus of regulatory discussions so far has been on PFOS and PFOA, with some discussion of GenX. But the more we dig, the more we see there are lots and lots of PFAS out there.”

Andrews noted that the pattern of constantly replacing one toxic chemical with another is a problem the federal government urgently needs to address. “The entire family of chemicals has a lot of similar characteristics,” he said.

“When these chemicals are stopped being produced, especially in significant quantities across the country, the levels go down,” Andrews said, referring to the corresponding drop in PFOS and PFOA levels in Americans’ blood after the compounds were phased out. “But it raises concerns about what’s going to happen next? Or are we actually being exposed to something that we’re not testing for?” “

The use of PFAS in firefighting foam has led to widespread environmental contamination across the United States, especially on or near military bases. Photo © iStockphoto.com | kzenon

Andrews and his co-author, Olga Naidenko, also an EWG scientist, continue to urge governments to consider a relatively low-hanging fruit: unnecessary PFAS use. “Even if someone makes the argument that for serious fires we need to use the best foam, I think we can all agree that there is no reason to spray PFAS just for training,” Naidenko said. “You can spray water.”

Environmental health advocates expressed hope that 2021 will bring greater progress on PFAS regulation. President-elect Joe Biden has pledged to set enforceable limits on PFAS in drinking water and designate PFAS as a hazardous substance—which would speed up cleanup of contaminated sites under the EPA’s Superfund program.

Breaking the Chain

Meanwhile, the million-dollar question (or, in fact, more) is: How do we remove PFAS from drinking water? The bond between carbon and fluorine atoms is one of the strongest in nature. As a result, PFAS degrade very slowly in nature. “People have called them ‘forever chemicals’ for good reason,” Sedlak says. “These carbon-fluorine bonds want to stay put.”

Because PFAS resist degradation, filtration is the primary strategy for removing them from drinking water. Granular activated carbon filters can absorb PFAS and other contaminants, although they must be replaced when all available surface area is taken up by the chemicals. Filters also tend to be less effective against short-chain PFAS than long-chain PFAS. Another removal method is ion-exchange resins, which can attract and hold negatively charged contaminants like PFAS. Perhaps the most effective technology to date is reverse osmosis. This approach can filter out a wide range of PFAS. At the same time, it comes at a prohibitively high price, says Heather Stapleton, a professor of environmental science and policy at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

Stapleton has researched different filters and found that all of them can work well. She installed one at home after discovering PFAS in her own drinking water. But that cost can be a significant barrier for many people, she notes, making it “an environmental justice issue.” The variety of PFAS compounds also poses a challenge. Community water systems can spend significant resources installing water treatment systems only to find that while the method may work well at removing one set of PFAS, it may not filter out another, Naidenko said. Scientists are studying more chemical and biological treatment methods. Sedlak is among researchers looking at ways to treat PFAS while it’s still in the ground, such as through in situ oxidation combined with bacteria to break down the chemicals. “What we know for sure is that we were exposed. What we don’t know is the long-term health impacts to us as a community” – Emily Donovan Joel Ducoste, a professor of civil, construction, and environmental engineering at NC State University in Raleigh, North Carolina, lamented that the treatment processes currently in use are still not able to remove PFAS and provide safe drinking water for Americans. “This is a problem in our state and is becoming a national problem,” he said. More solid science on PFAS – optimal treatments, truly safe alternatives, and potential health impacts – can’t come soon enough for those who face legacy PFAS contamination every day in Wilmington. “What we know for sure is that we were exposed. What we don’t know is the long-term health impacts on us as a community,” said Emily Donovan, co-founder of Clean Cape Fear, a grassroots group advocating for clean water in the area. Part of their effort, she said, is to seek better medical monitoring of people exposed to PFAS. Because of the long latency period between exposure and illness—often decades—it’s difficult to link any PFAS to specific cancers. Kennedy noted that his family has no history of breast cancer and no genetic predisposition to the disease. “Those factors make me even more convinced that PFAS is responsible,” he said. “It just doesn’t seem like the right way to test the safety of chemicals—the big underlying concern here—to expose the population at large. But that seems to be what we’re doing now,” Andrews said. https://ichi.pro/vi/tu-alaska-den-florida-cac-hop-chat-pfas-co-hai-gay-o-nhiem-nuoc-tai-nhieu-dia-diem-o-moi-182286968830018